Editor's Note: So you want to be healthy and jog. You carry some water with you in one of those trendy plastic bottles. Well, guess what? You're poisoning your body with a deadly chemical called BPA, added to make the plastic more pliable. What's more, it's used in your baby's bottle too! This is a

must read!

By Will DunhamPosted 2008/09/16 at 8:41 pm EDT

ROCKVILLE, Maryland, Sep. 16, 2008 (Reuters) -- A major study links a chemical widely used in plastic products, including baby bottles, to health problems in humans like heart disease and diabetes, but U.S. regulators said on Tuesday they still believe it is safe.

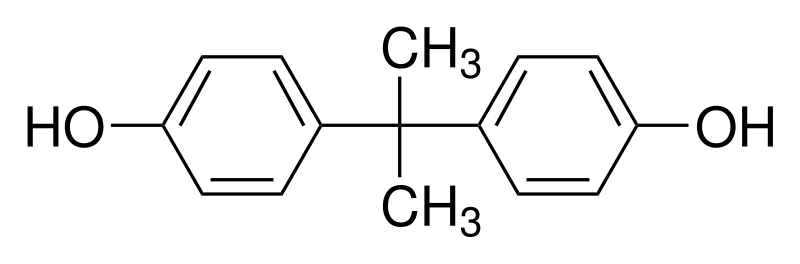

The chemical bisphenol A, or BPA, is commonly used in plastic food and beverage containers and in the coating of food cans.

Until now, environmental and consumer activists who have questioned the safety of BPA have relied on animal studies.

But the study by British researchers in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that among 1,455 U.S. adults, those with the highest levels of BPA were more likely to have heart disease, diabetes and liver-enzyme abnormalities than those with the lowest levels.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration officials said they would review the new findings, which were not yet published when the agency issued a draft conclusion in August that BPA is safe at current exposure levels.

"We have confidence in the data that we've looked at and the data that we're relying on to say that the margin of safety is adequate," FDA official Laura Tarantino said at a meeting of experts advising the agency on whether it made the right call.

"There are things you can do if you choose to reduce your level of bisphenol A," Tarantino said. "But we have not recommended that anyone change their habits or change their use of any of these products because right now we don't have the evidence in front of us to suggest that people need to."

Panel chairman Martin Philbert declined to say what the committee's next move would be.

BPA is used to make polycarbonate plastic, a clear shatter-resistant material in products ranging from baby bottles [right] to medical devices.

BPA is used to make polycarbonate plastic, a clear shatter-resistant material in products ranging from baby bottles [right] to medical devices.

BPA can mimic the hormone estrogen in the body.

LEACHING INTO LIQUIDS

People can consume BPA when it leaches out of the plastic into baby formula, water or food inside a container. Some retailers and manufacturers are moving away from products with BPA. Canadian officials have concluded BPA was harmful.

Steven Hentges of the American Chemistry Council, an industry group, said the study's design did not allow for anyone to conclude BPA causes heart disease and diabetes.

"On the other hand, though, bisphenol A has been very intensively studied in a very large number of laboratory animal studies. And the weight of evidence from those studies ... continues to support the safe use of products containing bisphenol A," he said in a telephone interview.

The British researchers, who acknowledged their findings are not proof that the chemical is causing the harm, analyzed urine samples from a U.S. government health survey of adults ages 18-74 representative of the U.S. population.

The 25 percent of people with the highest levels of bisphenol A in their bodies were more than twice as likely to have heart disease, including heart attacks or type 2 diabetes, compared to the 25 percent with the lowest levels.

At the FDA panel meeting, several scientists and activists said the FDA ignored animal studies finding health concerns and some called for the chemical to be banned in food containers.

Recently, researchers showed that when Agouti mice (mice that are all genetically-related) were fed prenatal diets high in BPA (a hormone-disrupting chemical found, for instance, in some plastics and the linings of some canned goods), those mice became obese—twice the weight of a normal mouse—and had increased risk of breast and prostate cancers (Dolinoy et al. 2007a). This finding has led scientists to develop the Environmental Obesogens / Diabesity Hypothesis: Pre-natal, early life and young life exposures to bisphenol A (BPA) activate fat receptors and stimulate fat cells, which predispose individuals to obesity and/or related metabolic disorders (diabesity). |

Democratic U.S. Rep. John Dingell of Michigan, who heads the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, said the FDA has "focused myopically on industry-funded research."

Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley, ranking member of the Committee on Finance, released a letter he wrote to FDA Commissioner Dr. Andrew von Eschenbach asking why the agency has not appointed a safety panel to review BPA.

Tarantino said nothing was ignored but industry-funded studies finding no harm were important in the conclusions. The panel is expected to present its advice to the FDA next month.

Tarantino, head of the FDA's office of food additive safety, said there is talk of government scientists doing their own BPA safety studies, but that could take years to conduct.

UPDATE: BPA Confirmed in Human Heart Disease and Diabetes!

ScienceDaily (Sep. 16, 2008) -- Higher levels of urinary Bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical compound commonly used in plastic packaging for food and beverages, is associated with cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and liver-enzyme abnormalities, according to a study in the September 17 issue of JAMA. This study is being released early to coincide with a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hearing on BPA.

BPA is one of the world's highest production-volume chemicals, with more than two million metric tons produced worldwide in 2003 and annual increase in demand of 6 percent to 10 percent annually, according to background information in the article. It is used in plastics in many consumer products.

"Widespread and continuous exposure to BPA, primarily through food but also through drinking water, dental sealants, dermal exposure, and inhalation of household dusts, is evident from the presence of detectable levels of BPA in more than 90 percent of the U.S. population," the authors write. Evidence of adverse effects in animals has created concern over low-level chronic exposures in humans, but there is little data of sufficient statistical power to detect low-dose effects. This is the first study of associations with BPA levels in a large population, and it explores "normal" levels of BPA exposure.

David Melzer, M.B., Ph.D., of Peninsula Medical School, Exeter, U.K., and colleagues examined associations between urinary BPA concentrations and the health status of adults, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2004. The survey included 1,455 adults, age 18 through 74 years, with measured urinary BPA concentrations.

The researchers found that average BPA concentrations, adjusted for age and sex, appeared higher in those who reported diagnoses of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. A 1-Standard Deviation (SD) increase in BPA concentration was associated with a 39 percent increased odds of cardiovascular disease (angina, coronary heart disease, or heart attack combined) and diabetes.

When dividing BPA concentrations into quartiles, participants in the highest BPA concentration quartile had nearly three times the odds of cardiovascular disease compared with those in the lowest quartile. Similarly, those in the highest BPA concentration quartile had 2.4 times the odds of diabetes compared with those in the lowest quartile.

In addition, higher BPA concentrations were associated with clinically abnormal concentrations for three liver enzymes. No associations with other diagnoses were observed.

"Using data representative of the adult U.S. population, we found that higher urinary concentrations of BPA were associated with an increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and liver-enzyme abnormalities. These findings add to the evidence suggesting adverse effects of low-dose BPA in animals. Independent replication and follow-up studies are needed to confirm these findings and to provide evidence on whether the associations are causal," the authors conclude. "Given the substantial negative effects on adult health that may be associated with increased BPA concentrations and also given the potential for reducing human exposure, our findings deserve scientific follow-up."

In accompanying editorial, Frederick S. vom Saal, Ph.D., of the University of Missouri, Columbia, and John Peterson Myers, Ph.D., of Environmental Health Sciences, Charlottesville, Va., comment on the findings regarding BPA.

"Since worldwide BPA production has now reached approximately 7 billion pounds per year, eliminating direct exposures from its use in food and beverage containers will prove far easier than finding solutions for the massive worldwide contamination by this chemical due its to disposal in landfills and the dumping into aquatic ecosystems of myriad other products containing BPA, which Canada has already declared to be a major environmental contaminant."

"The good news is that government action to reduce exposures may offer an effective intervention for improving health and reducing the burden of some of the most consequential human health problems. Thus, even while awaiting confirmation of the findings of Lang et al, decreasing exposure to BPA and developing alternatives to its use are the logical next steps to minimize risk to public health."

UPDATE: Canada bans bottles with BPA

TORONTO - Canada declared a chemical widely used in food packaging a toxic substance on Saturday and will now move to ban plastic baby bottles containing bisphenol A.

The toxic classification, issued in the Canada Gazette, makes Canada the first country to classify the chemical commonly used in the lining of food cans, eyeglass lenses and hundreds of household items, as risky.

"Many Canadians...have expressed their concern to me about the risks of bisphenol A in baby bottles," Environment Minister John Baird said in a statement. "Today's confirmation of our ban on BPA in baby bottles proves that our government did the right thing in taking action to protect the health and environment for all Canadians."

Canada's announcement came six months after its health ministry labeled BPA as dangerous. Health Minister Tony Clement said a report on bisphenol A has found the chemical endangers people, particularly newborns and infants, and the environment, citing concerns that the chemical in polycarbonate products and epoxy linings can migrate into food and beverages.

Baby bottles frequently contain BPA, used to harden plastic and make it shatterproof.

Several U.S. states are considering restricting BPA use, some manufacturers have begun promoting BPA-free baby bottles, and some stores are phasing out baby products containing the chemical. Wal-Mart Canada and other major retailers in Canada in recent months have begun removing BPA-based food-related products such as baby bottles and sipping cups from store shelves.

The scientific debate over BPA could drag on for years. The European Union and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration say the chemical is safe. However, the FDA is awaiting word from a scientific panel expected to deliver an independent risk assessment later this month.

The chemicals industry maintains that polycarbonate bottles contain little BPA and leach traces considered too low to harm humans.

Robert Brackett, chief science officer for the Grocery Manufacturers Association, said Friday that Canada's precautionary action regarding the use of BPA is disproportional to the risk determined by public health agencies.

The biggest concern with this widely used chemical, traces of which can be found in more than 90 percent of Americans, has been over BPA's possible effects on reproductive development and hormone-related problems.

Rochester Study Raises New Questions about Controversial Plastics Chemical

Richard W. Stahlhut, M.D., M.P.H.

A University of Rochester Medical Center study challenges common assumptions about the chemical bisphenol A (BPA), by showing that in some people, surprisingly high levels remain in the body even after fasting for as long as 24 hours. The finding suggests that BPA exposure may come from non-food sources, or that BPA is not rapidly metabolized, or both.

The journal Environmental Health Perspectives published the research online January 28, 2009.

Controversy around BPA is mounting. In December the U.S. Food and Drug Administration agreed to reconsider the health risks of the chemical, which is used to make plastic baby bottles, water bottles and many other consumer products. Scientific studies suggest that BPA may harm the brain and prostate glands in developing fetuses and infants; adults with higher BPA levels in their urine were linked to higher risks for heart disease and diabetes, according to a study published last September in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The latest finding from Rochester is important because, until now, scientists believed that BPA was excreted quickly and that people were exposed to BPA primarily through food. Indeed, the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority have declared BPA safe based, in part, on those assumptions.

"Our results simply do not fit that picture...The research community has clues that could help explain some of these results but to date the importance of the clues have been underestimated. We must chase them much more vigorously now."--Richard W. Stahlhut, M.D., M.P.H., of the University of Rochesterís Environmental Health Sciences Center.

Manufacturers use BPA to harden plastics in many types of products. In addition to plastic bottles, BPA is used in PVC water pipes and food storage containers. BPA also coats the inside of metal food cans, and is used in dental sealants.

Stahlhut and colleagues obtained data for a sample of 1,469 American adults through the Center for Disease Controlís National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).The researchers sought to explore the link between BPA urine concentration and the length of time a person had been fasting.

Accepting the widely held assumption that food is the most common route of exposure to BPA, Stahlhut expected to see a relationship between the last food ingested, fasting time, and BPA levels. People who had fasted longest (15 to 24 hours), for example, should have had much lower BPA levels than people who had eaten more recently, Stahlhut said.

Instead, those who fasted had levels that were only moderately lower than people who had just eaten. This is significant because scientists expected BPA levels to decrease by about half, every five hours.

"In our data, BPA levels appear to drop about eight times more slowly than expected ñ so slowly, in fact, that race and sex together have as big an influence on BPA levels as fasting time," Stahlhut said.

According to the authors, two possible explanations may exist for the higher-than-expected levels of BPA in people who fasted. One is that exposure to BPA might come through other means, such as house dust or tap water.

In addition, Stahlhut theorizes that BPA may seep into fat tissues, where it would be released more slowly. However, further study is needed to evaluate the effects of BPA on adipose tissue hormones and function, Stahlhut said, as well as more studies to compare BPA levels in fat versus blood and urine.

The Centers for Disease Control estimates that 93 percent of Americans have detectable levels of BPA in their urine.

The latest data also supports the idea that individuals might be re-exposed throughout the course of a day, Stahlhut said. In 2000 another research group found that BPA can migrate from PVC pipes or hoses into room temperature water, producing another potential route of exposure.

The University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Training Grant, funded the research.

# # #

Six Plastic Baby Bottle Manufacturers Quietly Remove Products From Market With BPA

March 2009

(NaturalNews) After years of insisting Bisphenol-A (BPA) posed no threat to the health of babies, six larger manufacturers of baby bottles have announced they will stop shipping new baby bottles made with the chemical. No existing baby bottles are being recalled, however. Nor are they being taken off the shelves of retailers. The baby bottles being purchased and used by babies right now still contain BPA, a hormone disruptor chemical linked to serious health problems like breast cancer and reproductive abnormalities.

As the Washington Post reports (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dy...), most of the six manufacturers only agreed to stop using BPA in their baby bottles after being contacted by Connecticut Attorney General Richard Blumenthal who asked (demanded?) the companies stop using the controversial chemical. No doubt these companies saw the writing on the wall and realized that if they didn't drop the chemical now, they could be facing a wave of class action lawsuits from angry mothers (and their mutant babies) in the years ahead.

The six companies that have agreed to stop using BPA in baby bottles sold in the U.S. are:

- Gerber

- Avent America, Inc

- Evenflo Co.

- Disney First Years

- Dr. Brown

- Playtex Products, Inc.

The BornFree company, of course, has been selling BPA-free baby bottles for years: www.NewBornFree.com

It's important to note here that these companies are all removing a chemical that they claim is perfectly safe. In other words, they're essentially saying, "It's not bad for ya, but we're takin' it out anyway." No doubt they have realized that admitting BPA is dangerous would unleash a flood of lawsuits. It's safer to just quietly take it out now, before there's any talk of lawsuits about mutant children growing adult breasts at age seven or other similar side effects.

The real health damage caused by BPA, after all, will take many years to become evident. And by that time, most people will have forgotten that baby bottle companies once used this chemical in their products.

Child Obesity Is Linked to Chemicals in Plastics

By Jennifer 8. Lee

Exposure to chemicals used in plastics may be linked with childhood obesity, according to results from a long-term health study on girls who live in East Harlem and surrounding communities that were presented to community leaders on Thursday by researchers at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

The chemicals in question are called phthalates, which are used to to make plastics pliable and in personal care products. Phthalates, which are absorbed into the body, are a type of endocrine disruptor -- chemicals that affect glands and hormones that regulate many bodily functions. They have raised concerns as possible carcinogens for more than a decade, but attention over their role in obesity is relatively recent.

The research linking endocrine disruptors with obesity has been growing recently. A number of animal studies have shown that exposing mice to some endocrine disruptors causes them be more obese. Chemicals that have raised concern include Bisphenol A (which is used in plastics) and perfluorooctanoic acid, which is often used to create nonstick surfaces.

However, the East Harlem study, which includes data published in the journal Epidemiology, presents some of the first evidence linking obesity and endocrine disruptors in humans.

The researchers measured exposure to phthalates by looking at the children's urine. "The heaviest girls have the highest levels of phthalates metabolites in their urine," said Dr. Philip J. Landrigan, a professor of pediatrics at Mount Sinai, one of the lead researchers on the study. "It goes up as the children get heavier, but it's most evident in the heaviest kids."

This builds upon a larger Mount Sinai research effort called "Growing Up Healthy in East Harlem," which has looked at various health factors in East Harlem children over the last 10 years, including pesticides, diet and even proximity to bodegas.

About 40 percent of the children in East Harlem are considered either overweight or obese. "When we say children, I'm talking about kindergarten children, we are talking about little kids," Dr. Landrigan said. "This is a problem that begins early in life."

The Growing Up Healthy study involves more than 300 children in East Harlem, and an additional 200 or so children in surrounding community.

The phthalate study follows a separate group of about 400 girls in the same communities, who range in age from 9 to 11.

One thing researchers have found is that the levels of phthalates measured in children in both studies are significantly higher than the average levels that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have measured for children across the entire United States.

The findings may presage a new approach to thinking about obesity -- drawing environmental factors into a central part of the equation. "Most people think childhood obesity is an imbalance between how much they eat and how much they play," Dr. Landrigan said.

But he thinks the impact of endocrine disruptors on obesity could be more significant than many people believe. "Most people think it's marginal," he said, paling in comparison with diet and exercise.

But he likened it with the impact of lead on a child's I.Q. "Lead never makes more than 3 or 4 percent difference in margin, but 3 to 5 I.Q. points is a big deal," he said.

Of course, at this stage, researchers cannot say if the exposure actually causes obesity, simply that it seems to be linked. "Right now it's a correlation; we donít know if it's cause and effect or an accidental finding," Dr. Landrigan said. "The $64,000 question is, what is causal pathway? Does it go through the thyroid gland? Does it change fat metabolism?"

The National Children's Study, which will follow 100,000 children from across the country from birth to age 21, will look more broadly at endocrine disruptors and other issues.

"Some of the clues that come out of East Harlem will actually be pursued in the larger one," Dr. Landrigan said.

Meanwhile, Dr. Landrigan advised people to reduce their exposure to phthalates as a precautionary measure. "You can't avoid them completely, but you can certainly reduce their exposure," he said.

It's somewhat difficult to do, since many things do not contain labels identifying phthalates, and in the case of perfumes they can simply be labeled as "fragrance."

Phthalates are found in certain personal care products (like nail polish and cosmetics), though recent regulation has encouraged companies to reduce or eliminate them.

They are also found in common everyday objects, including vinyl siding, toys and pacifiers. A number of environmental Web sites, including The Daily Green, have advised certain strategies, including learning to recognize the abbreviations for certain common phthalates and to prefer certain kinds of recyclable plastics over others.

Human Exposure To Controversial Chemical BPA May Be Greater Than Dose Considered Safe

ScienceDaily (June 11, 2009) ó People are likely being exposed to the commonly used chemical bisphenol A (BPA) at levels much higher than the recommended safe daily dose, according to a new study in monkeys.

The results will be presented Thursday at The Endocrine Society's 91st Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C.

"BPA is now known to be a potent estrogen," said Frederick vom Saal, PhD, a co-author of the new study and a professor of biological sciences at the University of Missouri-Columbia. "Human and animal studies indicate it could be related to diabetes, heart disease, liver abnormalities, miscarriage and other reproductive abnormalities, as well as prostate and breast cancer."

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declared BPA is safe based on estimates that people consume only small amounts each day from food. However, recent research indicated that U.S. adults are exposed to more BPA from multiple sources than previously thought, vom Saal said.

BPA is found in polycarbonate plastic food and beverage containers, such as water and infant bottles, as well as in the epoxy resin lining of cans and other sources. The chemical can leach into food and beverages, according to the National Institutes of Health, which funded the study by vom Saal and colleagues.

"Between 8 and 9 billion pounds of BPA are used in products every year," vom Saal said.

In their study, he and his colleagues fed five female adult monkeys an oral dose of BPA (400 micrograms per kilogram of body weight). This amount is more than 400 times higher than the amount that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that human adults are exposed to and 8 times higher than the estimated safe daily amount to consume, according to vom Saal.

Yet the blood levels of biologically active BPA over the next 24 hours were lower in the monkeys than the average levels found in people in the United States and other developed countries, vom Saal said. For levels to be higher in people when measured, their exposure dose must be greater than that given to the monkeys, he explained.

"These results suggest that the average person is likely exposed to a daily dose of BPA that far exceeds the current estimated safe daily intake dose," vom Saal said.

He said that BPA exposure must come from many unknown sources, in addition to food and beverage containers. Like drugs, BPA acts in pulses, with each exposure creating a high-level pulse before it is cleared in the urine, according to vom Saal.

The researchers are continuing the study in more monkeys, but vom Saal said they do not expect to get different findings because the data in the first five animals were "very consistent." The species of monkey that they used (rhesus) metabolizes BPA similar to humans, he added.

Workplace BPA Exposure Increases Risk Of Male Sexual Dysfunction

High levels of workplace exposure to Bisphenol-A may increase the risk of reduced sexual function in men, according to a Kaiser Permanente study appearing in the journal Human Reproduction.

The five-year study examined 634 workers in factories in China, comparing workers in BPA manufacturing facilities with a control group of workers in factories where no BPA was present. The study found that the workers in the BPA facilities had quadruple the risk of erectile dysfunction, and seven times more risk of ejaculation difficulty.

This is the first research study to look at the effect of BPA on the male reproductive system in humans. Previous animal studies have shown that BPA has a detrimental effect on male reproductive system in mice and rats.

Funded by the U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, this study adds to the body of evidence questioning the safety of BPA, a chemical made in the production of polycarbonated plastics and epoxy resins found in baby bottles, plastic containers, the lining of cans used for food and beverages, and in dental sealants.

The BPA levels experienced by the exposed factory workers in the study were 50 times higher than what the average American male faces in the United States, the researchers said.

"Because the BPA levels in this study were very high, more research needs to be done to see how low a level of BPA exposure may have effects on our reproductive system," said the study's lead author. De-Kun Li, MD, Ph.D., a reproductive and perinatal epidemiologist at Kaiser Permanente's Division of Research in Oakland, Calif. "This study raises the question: Is there a safe level for BPA exposure, and what is that level? More studies like this, which examine the effect of BPA on humans, are critically needed to help establish prevention strategies and regulatory policies."

The researchers explained that BPA is believed by some to be a highly suspect human endocrine disrupter, likely affecting both male and female reproductive systems. This first epidemiological study of BPA effects on the male reproductive system provides evidence that has been lacking as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and various U.S. government panels have explored this controversial topic.

This study is the first of series of studies that examine the BPA effect in humans and are to be published by Dr. Li and his colleagues.

The study finding, Dr. Li also points out, may have implications of adverse BPA effects beyond male sexual dysfunction. Male sexual dysfunction could be a more sensitive early indicator for adverse BPA effects than other disease endpoints that are more difficult to study, such as cancer or metabolic diseases.

For this study, researchers compared 230 workers exposed to high levels of BPA in their jobs as packagers, technical supervisors, laboratory technicians and maintenance workers in one BPA manufacturing facility and three facilities using BPA to manufacture epoxy resin, in several regions near Shanghai, to a control group of 404 workers in the same city from factories where no BPA exposure in the workplace was recorded. The factories with no BPA exposure produced construction materials, water supplies, machinery, garments, textiles, and electronics. The workers from the two groups were matched by age, education, gender, and employment history.

Researchers gauged BPA levels by conducting spot air sampling, personal air sample monitoring and walk-through evaluations, by reviewing factory records and interviewing factory leaders and workers about personal hygiene habits, use of protective equipment, and exposures to other chemicals. A subset of workers also provided urine samples for assaying urine BPA level to confirm the higher BPA exposure level among the workers with occupational BPA exposure.

Researchers measured sexual function based on in-person interviews using a standard male sexual function inventory that measures four categories of male sexual function including erectile function, ejaculation capability, sexual desire, and overall satisfaction with sex life.

After adjusting for age, education, marital status, current smoking status, a history of chronic diseases and exposure to other chemicals, and employment history, the researchers found the BPA-exposed workers had a significantly higher risk of sexual dysfunction compared to the unexposed workers.

The BPA-exposed workers had a nearly four-fold increased risk of reduced sexual desire and overall satisfaction with their sex life, greater than four-fold increased risk of erection difficulty, and more than seven-fold increased risk of ejaculation difficulty.

A dose-response relationship was observed with an increasing level of cumulative BPA exposure associated with a higher risk of sexual dysfunction. Furthermore, compared to the unexposed workers, BPA-exposed workers reported significantly higher frequencies of reduced sexual function within one year of employment in the BPA-exposed factories.

Mother's Exposure to Bisphenol A May Increase Children's Chances of Asthma

February 4, 2010: As reported in ScienceDaily, for years, scientists have warned of the possible negative health effects of bisphenol A, a chemical used to make everything from plastic water bottles and food packaging to sunglasses and CDs. Studies have linked BPA exposure to reproductive disorders, obesity, abnormal brain development as well as breast and prostate cancers, and in January the Food and Drug Administration announced that it was concerned about "the potential effects of BPA on the brain, behavior and prostate gland of fetuses, infants and young children."

Now, mouse experiments by University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston researchers have produced evidence that a mother's exposure to BPA may also increase the odds that her children will develop asthma. Using a well-established mouse model for asthma, the investigators found that the offspring of female mice exposed to BPA showed significant signs of the disorder, unlike those of mice shielded from BPA.

"We gave BPA in drinking water starting a week before pregnancy, at levels calculated to produce a body concentration that was the same as that in a human mother, and continued on through the pregnancy and lactation periods," said UTMB associate professor Terumi Midoro-Horiuti, lead author of a paper on the study appearing in the February issue of Environmental Health Perspectives.

Four days after birth, the researchers sensitized the baby mice with an allergy-provoking ovalbumin injection, followed by a series of daily respiratory doses of ovalbumin, the main protein in egg white. The investigators then measured levels of antibodies against ovalbumin and quantities of inflammatory white blood cells known as eosinophils in the lungs of the mouse pups. They also used two different methods to measure lung function.

"What we were looking for is the asthma response to a challenge, something like what might happen if you had asthma and got pollen in your nose or lungs, you might have an asthma attack," said UTMB professor Randall Goldblum, also an author of the paper. "All four of our indicators of asthma response showed up in the BPA group, much more so than in the pups of the nonexposed mice."

The UTMB researchers said that although more work is needed to determine the precise mechanism of that response, it almost certainly has its roots in the property of BPA thought to contribute to other health problems: its status as an "environmental estrogen." Environmental estrogens are natural or artificial chemicals from outside the body that when consumed mimic the hormone estrogen, activating its powerful biochemical signaling networks in often dangerous ways. In a 2007 Environmental Health Perspectives paper, for example, Midoro-Horiuti, Goldblum and UTMB professor and current study co-author Cheryl Watson described how adding small amounts of environmental estrogens into cultures of human and mouse mast cells -- common immune cells packed with allergic response-inducing chemicals such as histamine -- produced a sudden release of allergy-promoting substances.

"Our results show that we have to consider the possible impact of environmental estrogens on normal immune development and on the development and morbidity of immunologic diseases such as asthma," Midoro-Horiuti said. "We also need to look at doing more epidemiological studies directly in humans, which is possible because BPA is so prevalent in the environment -- all of us are already loaded with it to a varying extent. For example, it should be possible to determine if children who have more BPA exposure are more likely to develop asthma."

In addition to Midoro-Horiuti, Goldblum and Watson, UTMB postdoctoral fellow Ruby Tiwari is also an author of the paper, titled "Maternal Bisphenol A Exposure Promotes the Development of Experimental Asthma in Mouse Pups." The National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences and the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease supported this research.

Why BPA Leached from 'Safe' Plastics May Damage Health of Female Offspring

Here's more evidence that "safe" plastics are not as safe as once presumed: New research published online in The FASEB Journal suggests that exposure to Bisphenol A (BPA) during pregnancy leads to epigenetic changes that may cause permanent reproduction problems for female offspring. BPA, a common component of plastics used to contain food, is a type of estrogen that is ubiquitous in the environment.

"Exposure to BPA may be harmful during pregnancy; this exposure may permanently affect the fetus," said Hugh S. Taylor, Ph.D., co-author of the study from Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. "We need to better identify the effects of environmental contaminants on not just crude measures such as birth defects, but also their effect in causing more subtle developmental errors."

Taylor and colleagues made this discovery by exposing fetal mice to BPA during pregnancy and examining gene expression and DNA in the uteruses of female fetuses. Results showed that BPA exposure permanently affected the uterus by decreasing regulation of gene expression. These epigenetic changes caused the mice to over-respond to estrogen throughout adulthood, long after the BPA exposure. This suggests that early exposure to BPA genetically "programmed" the uterus to be hyper-responsive to estrogen. Extreme estrogen sensitivity can lead to fertility problems, advanced puberty, altered mammary development and reproductive function, as well as a variety of hormone-related cancers. BPA has been widely used in plastics and other materials. Examples include use in water bottles, baby bottles, epoxy resins used to coat food cans, and dental sealants.

"The BPA baby bottle scare may be only the tip of the iceberg." said Gerald Weissmann, M.D., Editor-in-Chief of The FASEB Journal. "Remember how diethylstilbestrol (DES) caused birth defects and cancers in young women whose mothers were given such hormones during pregnancy. We'd better watch out for BPA, which seems to carry similar epigenetic risks across the generations. "

| Reader's Comments: Thanks for the info. I am worried about other plastics, like Coca Cola bottles and the clear wrap that I use to cover food in my refrigerator. OMG! P.Guarette

I have some bad news for everyone. This plastic is used to transport bulk ingredients used in almost every prepared food. I work in a commercial kitchen and its EVERYWHERE! No wonder the EPA is dragging their feet. Keith N.

I stopped using those water bottles because sometimes I could taste the plastic. I wonder how many people and babies are sick from this. It's too bad that this is yet another example of the "Bush Business Administration" dropping the ball. What do they care, though. We don't make over a million annually. We're the "low class" and we're only good as long as we keep buying the shit that companies keep producing without careful testing. We're as bad as China! gr8Bd

I'm speechless. When will it stop? Now you can't even trust the containers to be free from poison! What can we do? Anonymous

|