"The god himself was a statue. The statue was not of a god (as we would say) but the god himself." -- Julian Jaynes

The bicameral (hallucinated) voice provided morality, intuition and survival skills. Despite some really harsh times, the guidance of the voice was sufficient enough to allow humanity to survive until today.

Through ice ages, changing climates, famines, droughts, migrations and diseases, the bicameral voice was a good shepherd to humanity.

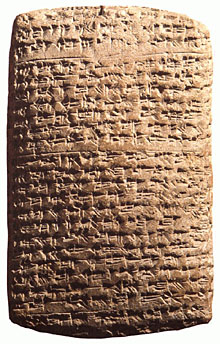

Controlled by a common voice, larger groups of diverse humans began to live and cooperate together. At some point, the necessity of writing imposed itself on bicameral man. At first symbols or small pictures were drawn to represent some object. Later these became condensed to a few unique lines, impressed in clay. The first widely used writing system was invented by the Sumerians, called cuneiform.

Controlled by a common voice, larger groups of diverse humans began to live and cooperate together. At some point, the necessity of writing imposed itself on bicameral man. At first symbols or small pictures were drawn to represent some object. Later these became condensed to a few unique lines, impressed in clay. The first widely used writing system was invented by the Sumerians, called cuneiform.

All of the great Mesopotamian civilizations used cuneiform (the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Elamites, Hatti, Hittites, Assyrians, Hurrians and others) until it was abandoned in favor of the alphabetic script at some point after 100 BCE.

Archaeologists have uncovered thousands of clay tablets containing cuneiform texts from different eras. This gives us an interesting way of gaging the people for evidence of consciousness.

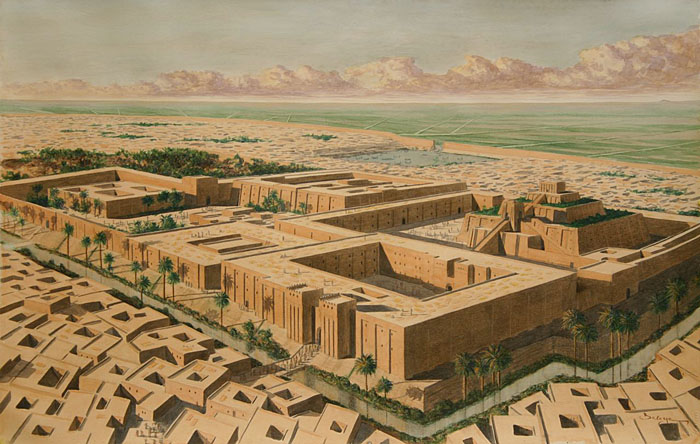

Cuneiform was established in one of the first cities ever -- Uruk (Iraq) in 3200 BCE. Before then there were just small villages made up of extended families and tribes. The legends I'm going to discuss had their origins in these times before writing.

Below is an illustration of what the first city (Ur) looked like. You will notice the tall ziggurat pyramid. That is where the voice of authority resided -- the city's god.

To maintain the guidance and influence for the population, the voice that ruled the city was housed in an elevated shrine, visible (and therefore audible) to everyone who served it. As Jaynes put it:

"Throughout Mesopotamia, from the earliest times of Sumer and Akkad, all lands were owned by gods and men were their slaves. Of this, the cuneiform texts leave no doubt whatever. Each city-state had its own principal god, and the king was described in the very earliest written documents that we have as 'the tennant farmer of the god.'The god himeslf was a statue. The statue was not of a god (as we would say) but the god himself. He even had his own house, called by Sumerians the 'great house'. It formed the center of the complex of temple buildings...

Everywhere in these texts, it is the speech of gods who decide what is to be done... It is not human beings who are the rulers, but the hallucinated voices of the gods Kadi, Ningirsu, and Enlil..."

Most of the Sumerian texts that were translated turned out to be simple inventories. Some were records of taxes paid to the god's keepers or deposits of grains in a common granary. Many more were votives to the god, giving praise and thanks for the good harvest.

"... councillor, exceeding wise commander, princess of all great gods, exalted speaker, whose utterance is unrivaled." -- votive cuneiform text to the goddess NinegalNoticeably missing in these votives are personal requests. The favor of the gods determines one's needs and how they are met. Bicameral man did not think of himself. He had no self.

Among the cuneiform texts that were uncovered there were some significant stories, part history and part mythology. The most significant one is The Epic of Gilgamesh.

Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh was one of the first stories found on many different shards of clay when archaeologists excavated the ancient city of Uruk. It appears to be a compilation of stories that were much older and likely were passed along through oral tradition. Some of the repeating lines in the Epic of Gilgamesh resemble a musical chorus. So the original stories might have been sung before they were written down. The Epic of Gilgamesh is considered the first great work of literature

The Epic of Gilgamesh was one of the first stories found on many different shards of clay when archaeologists excavated the ancient city of Uruk. It appears to be a compilation of stories that were much older and likely were passed along through oral tradition. Some of the repeating lines in the Epic of Gilgamesh resemble a musical chorus. So the original stories might have been sung before they were written down. The Epic of Gilgamesh is considered the first great work of literature

Gilgamesh was a real king of Uruk, Mesopotamia, sometime between 2800 and 2500 BC. He is the main character. The story is biographical and lacks any personal commentary or narratives. The story contains emotions like anger, lust, pride and sadness, but these are mentioned only as motives that drive Gilgamesh throughout the adventure.

In the epic, Gilgamesh is a demigod of superhuman strength who built the city walls of Uruk to defend his people. His style of ruling is harsh and the story tells of the common people petitioning the gods to stop Gilgamesh from micromanaging their lives. The gods hear these pleas and decide that Gilgamesh needs someone of equal status to occupy his interests.

The gods create Enkidu and place him in the wilderness outside Uruk. At first, Enkidu eats grass and drinks from the lake like the other animals. He is accepted as one of them. When Gilgamesh learns about Enkidu he sends a harlot to have sex with him, at which point the animals reject him.

Eventually Enkidu and Gilgamesh become great friends. They travel on many quests together until, quite unexpectedly, Enkidu dies. Gilgamesh is both sad and angry and becomes determined to find the cure for death.

In his quest, he learns that there is a sage called Utanapishtim, who survived the Great Flood and is immortal. Yes, this is the Biblical Noah whose story was later incorporated into the Book of Genesis. This older story of Noah contains more interesting details (read the text here).

Gilgamesh eventually meets Utanapishtim and asks him for the secret of immortality but Utanapishtim (Noah) warns him that man was not meant to be immortal. Gilgamesh persists and is finally told that he must gather and eat a special plant from the bottom of the ocean. He ties rocks to his feet, enters the ocean and finds the plant but, upon reaching the shore he is too tired to eat it and falls asleep. When he awakens he sees that a snake has eaten the plant and all that remains is the old skin that the snake shed.

Throughout the story there are messages from the gods and many strange god-like creatures that speak to Gilgamesh. What is lacking is any clue about what is happening in the mind of the king. All decisions come from either dreams that must be interpreted by a seer or by audio hallucinations.

While we're talking about the story of the flood, another cuneiform text, Atrahasis, tells of the gods, high atop their ziggurat house, getting angry with the constant noise of the surrounding humans engaging in sex and loud yelling.

"The people became numerous...

The god was depressed by their uproar

Enlil heard their noise,

He exclaimed to the great gods

The noise of mankind has become burdensome..."

Because of bicameral man's increasingly unchecked promiscuity and loudness, Enlil, the chief god (voice) decrees that humanity will be eliminated. He tries to kill mankind by plagues then famines and finally by a flood.

Circumcision... penile mutilation to curb promiscuity

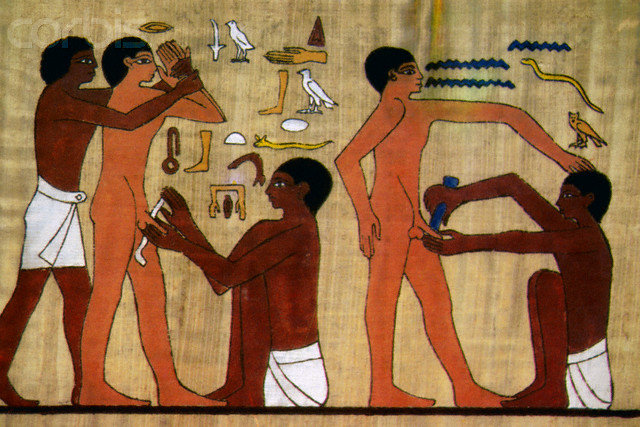

It is easy to imagine that bicameral men would have little advantage in regulating the expression of their natural urge to mate. The frequent mention of prostitutes and harlots in the ancient texts attests to the lack of shame or negative consequences that were associated with the sex act. One theory claims this is when the idea of mutilating a man's sexual organ, to reduce the pleasurable stimulation, became popular. Evidence suggests that circumcision was practiced in the Arabian Peninsula by the 4th millennium BCE, when the Sumerians and the Semites moved into the area that is modern-day Iraq. The earliest historical record of circumcision comes from Egypt, in the form of an image of the circumcision of an adult carved into the tomb of Ankh-Mahor at Saqqara, dating to about 2400-2300 BCE. Circumcision was done by the Egyptians to reduce masturbation and make the men of the kingdom engage in more constructive activities. Certainly, only a man with no consciousness, obedient to some guiding voice, could have submitted to this! Ancient circumcision was not severe and removed a smaller portion of the foreskin. Modern mutilation (circumcision) removes 70% of the nerves that would ordinarily stimulate sexual pleasure. It was widely performed on bicameral men to reduce sexual urges and, for some questionable reasons, is still inflicted in modern times on males on a global scale. Some studies have suggested that satisfaction from sex is dramatically reduced in circumcised men, leading to an unsettled urge and, in modern men with consciousness, this creates a greater preoccupation with sexual activities than natural, uncircumcised men. Update: 2015 -- In a just released report, circumcision has been linked with autism and attention deficit disorders.

|

So far in this story, we're within a few thousand years of the big change in human thinking that happens around 1000 BCE. In the Epic of Gilgamesh we saw the absence of consciousness in that there was no introspection or inner narration. The story was factual and the characters were objective. Further, all the decisions, thinking and reasoning was done either through a dream or by the hallucinated voice of the god.

I will discuss Egypt next, including the historical accounts written about these times in the Old Testament. Will we find the voice of gods telling men what to do there? The best is yet to come. (Now where is that pipe...)