So often we take our hands for granted. Consider how many portraits and photographs focus on out head while a majority of what we do and who we are -- our work and expression -- is the result of our contact with the outside world through our hands. More than any other part of our body, our hands are anatomical structures that create and maintain civilization. Before there was spoken language, there were gestures and hand signs.

What do we really know about our hands?

Ruth Propper and colleagues from Montclair State University have just published a paper in the journal, PLOS ONE (April 2013), which demonstrates the previously unknown use of hands in improving memory.

Participants in the research study were split into groups and asked to first memorize, and later recall words from a list of 72 random words. It's a daunting task under normal circumstances, unless you are a trained memory expert, which the participants were not.

In the experiment there were 4 groups who clenched their hands; One group clenched their right fist for about 90 seconds immediately prior to memorizing the list and then did the same immediately prior to recollecting the words. Another group clenched their left hand prior to both memorizing and recollecting. Two other groups clenched one hand prior to memorizing (either the left or right hand) and the opposite hand prior to recollecting. A control group did not clench their fists at any point.

So what happened?

The group that clenched their right fist when memorizing the list and then clenched the left when recollecting the words performed better than all the other hand clenching groups.

According to Ruth Propper, lead scientist,

"The findings suggest that some simple body movements -- by temporarily changing the way the brain functions -- can improve memory. Future research will examine whether hand clenching can also improve other forms of cognition, for example verbal or spatial abilities." [1]

The authors say that further work is needed to test whether their results with word lists also extend to memories of visual stimuli like remembering a face, or spatial tasks, or where keys, iPhone or the TV remote were placed. Based on previous work, the authors suggest that this effect of hand-clenching on memory may be because clenching a fist activates specific brain regions (left prefrontal cortex) that are also associated with memory formation.

But we can all try this experiment for ourselves. Here's how:

- Get a any magazine or newspaper article and black out any names or places in the text.

- Select a number, say 5, and then copy every 5th word to a paper until you have a few dozen. The experiment used 72 words but your list can vary.

- Use this list as your more-or-less "random" list and try the above experiment with your friends and family.

Some interesting questions are how the test results vary in left-handed v. right-handed individuals... maybe you can find a difference. But remember to have a control... someone who performs the test without making a fist. Compare the results. Let me know what you find [report at bottom of this page].

Clenching Left Hand Helps Athletes Avoid Choking Under Pressure

Some athletes may improve their performance under pressure simply by squeezing a ball or clenching their left hand before competition to activate certain parts of the brain, according to new research published by the American Psychological Association.

One doesn't have to be an athlete to have stress in today's world so this research should interest anyone who has to "get it together" and function at their peak levels.

One doesn't have to be an athlete to have stress in today's world so this research should interest anyone who has to "get it together" and function at their peak levels.

In three experiments with experienced soccer players, judo experts and badminton players, researchers in Germany tested the athletes' skills during practice and then in stressful competitions before a large crowd or video camera.

Right-handed athletes who squeezed a ball in their left hand before competing were less likely to choke under pressure than right-handed players who squeezed a ball in their right hand. The study was published online in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General (September 2012).

Juergen Beckmann, PhD, chair of sport psychology at the Technical University of Munich in Germany, explains the phenomenon.

"Rumination (i.e. thinking too deeply about their performance) can interfere with concentration and performance of motor tasks. Athletes usually perform better when they trust their bodies rather than thinking too much about their own actions or what their coaches told them during practice. While it may seem counterintuitive, consciously trying to keep one's balance is likely to produce imbalance, as was seen in some sub-par performances by gymnasts during the Olympics in London."

Essentially, Dr. Beckman is saying that athletes should trust their muscle memory and clear their minds by squeezing a ball.

Previous research has shown that rumination is associated with the brain's left hemisphere, while the right hemisphere is associated with superior performance in automated behaviors, such as those used by some athletes. The right hemisphere controls movements of the left side of the body, and the left hemisphere controls the right side. The researchers theorized that squeezing a ball or clenching the left hand would activate the right hemisphere of the brain and reduce the likelihood of the athlete's choking under pressure.

The study focused exclusively on right-handed athletes because some relationships between different parts of the brain aren't as well understood for left-handed people, according to the authors.

In fact, there is quite a spectrum of left-handedness. Some "lefties" only write with the left hand but play golf, hold a bat and do other activities with their right hand. Some left handed people can read backwards or upside down, some can not.

"The research could have important implications outside athletics. Elderly people who are afraid of falling often focus too much on their movements, so right-handed elderly people may be able to improve their balance by clenching their left hand before walking or climbing stairs.""Many movements of the body can be impaired by attempts at consciously controlling them," he said. "This technique can be helpful for many situations and tasks." -- Beckmann

Details of the Experiment In the first experiment, 30 semi-professional male soccer players took six penalty shots during a practice session. The next day, they attempted to make the same penalty shots in an auditorium packed with more than 300 university students waiting to see a televised soccer match between Germany and Austria. The players who squeezed a ball with their left hand performed as well under pressure as during practice, while players who squeezed a ball in their right hand missed more shots in the crowded auditorium. Twenty judo experts (14 men and six women) took part in the second experiment. First, they performed a series of judo kicks into a sandbag during practice. During a second session, they were told that their kicks would be videotaped and evaluated by their coaches. The judo athletes who squeezed a ball with their left hand not only didn't choke under pressure, they performed better overall during the stressful competition than during practice, while those in the control group choked under pressure, the study found. The final experiment featured 18 experienced badminton players (12 men and six women) who completed a series of practice serves. Then, they were divided into teams and competed against each other while being videotaped for evaluation by their coaches. Athletes who squeezed a ball in their left hand didn't choke under pressure, unlike the control group players who squeezed a ball in their right hand. A final phase of the experiment had the athletes just clench their left or right hand without a ball before competition, and players who clenched their left hand performed better than players who squeezed their right hand. |

This ball-squeezing technique probably wouldn't help athletes whose performance is based on strength or stamina, such as weightlifters or marathon runners. The effects apply to athletes whose performance is based on accuracy and complex body movements, such as soccer players or golfers [2].

Is Your Left Hand More Motivated Than Your Right Hand?

According to Mathias Pessiglione, of the Brain & Spine Institute in Paris (Sepember 2010) motivation doesn't have to be conscious. Your brain can decide how much it wants something without input from your conscious mind! This new study shows that both halves (hemispheres) of your brain don't even have to agree. Motivation can happen in one side of the brain at a time.

Once again, we are reminded that the brain is actually TWO brains that cooperate, or not, to perform different tasks in our daily life. Which half does which job is largely what determines our personality.

Here are the traits of each hemisphere per Roger Sperry (1973):

|

LEFT BRAIN FUNCTIONS |

RIGHT BRAIN FUNCTIONS |

Psychologists used to think that motivation was a conscious process. You know you want something, so you try to get it. But a few years ago experiments showed that motivation could be subconscious; when people saw subliminal pictures of a reward, even if they didn't know what they'd seen, they would try harder for a bigger reward.

Back in the 1950s, cinemas across the coulnry were successfully inserting frames into their shows that were viewed for only a fraction of a second (1/16th) but were able to prompt viewers to buy Coca-Cola or popcorn. So-called subliminal advertising showed the strength of sub-conscious motivation.

In an earlier study, volunteers were shown pictures of either a one-Euro coin or a one-Cent coin for a tiny fraction of a second. They did not perceive it consciously. Then they were told to squeeze a pressure-sensing handgrip. The harder they squeezed the grip, the more of the "coin" they would get. The image was subliminal, so volunteers didn't know how big a coin (or its value) they were squeezing for, but they would still squeeze harder for one euro than one cent. That result showed that motivation didn't have to be conscious.

The New Study

For the new study, researchers wanted to know if one side of the brain could be motivated at a time.

The test started with having the subject focus on a cross in the middle of the computer screen. Then the motivational coin -- one euro or one cent -- was shown on one side of the visual field. People were only subliminally motivated when the coin appeared on the same side of the visual field as the squeezing hand. For example, if the coin was on the right and they were squeezing with the right hand, they would squeeze harder for a euro than for a cent. But if the subliminal coin appeared on the left and they were squeezing on the right, they wouldn't squeeze any harder for a euro.

Remember that the right side of the brain controls the left side of the body and visa versa.

"The research shows that it's possible for only one side of the brain, and thus one side of the body, to be motivated at a time. It changes the conception we have about motivation. It's a weird idea, that your left hand, for instance, could be more motivated than your right hand. This basic research helps scientists understand how the two sides of the brain get along to drive our behavior." [3]

Are Emotions Reversed in Left-Handers' Brains?

According to Daniel Casasanto and Geoffrey Brookshire of The New School for Social Research in New York (May 2012), the way we use our hands may determine how emotions are organized in our brains.

In a recent study published in PLoS ONE, psychologists explain how emotions are classified as either "approach motivated" (i.e. wanting something) or withdraw (avoid) motivation. Consider your feelings about having a good meal verses, say, paying taxes.

Motivation, the drive to approach or withdraw from physical and social stimuli, is a basic building block of human emotion and socialization. For decades, scientists have believed that approach motivation is computed mainly in the left hemisphere of the brain, and withdraw motivation in the right hemisphere.

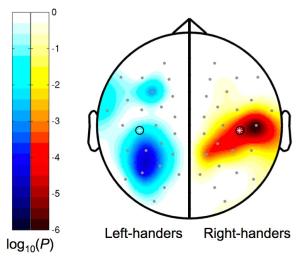

A new study challenges this idea, showing that a well-established pattern of brain activity, found across dozens of studies in right-handers, completely reverses in left-handers.

The study used electroencepahlography (EEG) to compare activity in participants' right and left hemispheres during rest. After having their brain waves measured, participants completed a survey measuring their level of approach motivation, a core aspect of our personalities.

[Above: In right-handers, stronger approach motivational tendencies predicted more neural activity in the left hemisphere. In left-handers, the pattern was reversed. The significance of the interaction of Hemisphere with Approach Tendency is plotted separately for left-handers (blue) and right-handers (red).]

In right-handers, stronger approach motivation was associated with greater activity in the left hemisphere than the right, consistent with previous studies. But... Left-handers showed the opposite pattern: approach motivation was associated with greater activity in the right hemisphere than the left.

Why is this so weird?

Most cognitive functions do not reverse with handedness. Language, for example, is mainly in the left hemisphere for the majority of right- and left-handers. But these results were not unexpected.

"We predicted this hemispheric reversal because we observed that people tend to use different hands to perform approach- and avoidance-related actions... Approach actions are often performed with the dominant hand, and avoidance actions with the non-dominant hand.""Approach motivation is computed by the hemisphere that controls the right hand in right-handers, and by the hemisphere that controls the left hand in left-handers ... We don't think this is a coincidence. Neural circuits for motivation may be functionally related to circuits that control hand actions -- emotion may be built upon neural circuits for action, in evolutionary or developmental time."

Daniel Casasanto, co-Author

Implications for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders

To treat depression and anxiety disorders, brain stimulation is used to increase neural activity in the patient's left hemisphere, long believed to the 'approach motivation hemisphere'.

"Given what we show here, this treatment, which helps right-handers, may be detrimental to left-handers -- the exact opposite of what they need.""The discovery that approach motivation reverses with handedness may lead to safer, more effective neural therapies for left-handers. It's something we're investigating now."

--Brookshire, co-Author [4]

Right-Handedness Prevailed 500,000 Years Ago!

According to a report in ScienceDaily, right-handedness is a distinctively human characteristic, with right-handers outnumbering lefties nine-to-one. But how far back does right-handedness reach in the human story? And how would you determine this?

Researchers have tried looking at ancient tools, prehistoric art and human bones, but the results have not been definitive. Ancient imprints of hands, such as produced by spattering pigment around the fingers, raises the question of which hand was dominant -- the hand being outlined or the hand doing the spatter?

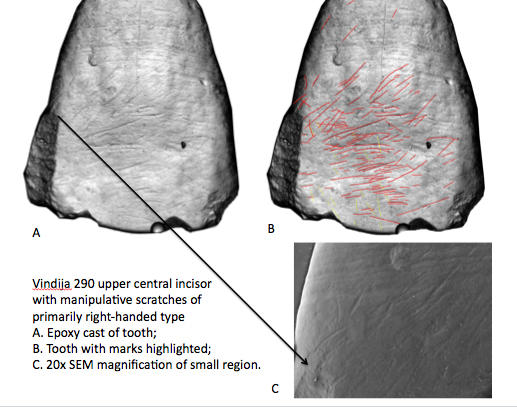

Now, David Frayer, professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas, has used markings on fossilized human front teeth to show that right-handedness goes back more than 500,000 years.

A study published in the British journal Laterality shows that distinctive markings on fossilized teeth correlate to the right or left-handedness of individual prehistoric humans.

Just imagine yourself chewing on a bone. The angle of your bite marks would be different depending upon which hand held the bone.

"The patterns seen on the fossil teeth are directly and consistently produced by right or left hand manipulation in experimental work."

-- Frayer, Author of study

The oldest teeth come from a more than 500,000-year-old cave chamber known as Sima de los Huesos near Burgos, Spain. It contains the remains of humans believed to be ancestors of European Neandertals. Other teeth studied by Frayer come from later Neandertal populations in Europe.

"These marks were produced when a stone tool was accidentally dragged across the labial face in an activity performed at the front of the mouth. The heavy scoring on some of the teeth indicates the marks were produced over the lifetime of the individual and are not the result of a single cutting episode."

Overall, Frayer and his co-authors found right-handedness in 93.1 percent of individuals sampled from the Sima de los Huesos and European Neandertal sites.

"It is difficult to interpret these fossil data in any way other than that laterality was established early in European fossil record and continued through the Neandertals. This establishes that handedness is found in more than just recent Homo sapiens." [5]

Frayer said that his findings on right-handedness have implications for understanding the language capacity of ancient populations, because language is primarily located on the left side of the brain, which controls the right side of the body, there is a right handedness-language connection.

"The general correlation between handedness and brain laterality shows that human brains were lateralized in a 'modern' way by at least half a million years ago and the pattern has not changed since then. There is no reason to suspect this pattern does not extend deeper into the past and that language has ancient, not recent, roots."

Left Handedness in Sports and Athletics

Studies have found that there are fewer left handed athletes in sports that require teamwork and cooperation. Sports like basketball and football are excellent examples. Left handers make up only about 17% of these teams. But if we look at sports requiring individual skills, things like boxing and baseball, left handers make up a majority of 50%. [6]

There must be a good reason that evolution has allowed people to be left handed -- and at a fairly consistent rate of about 10% -- in the general population. Perhaps they can do some useful things that right handed people cannot do... or maybe the fact that they are right-brain dominant is the factor that makes them unique. More research is needed to answer these questions.

[2] Jurgen Beckmann, Peter Gropel, Felix Ehrlenspiel. Preventing Motor Skill Failure Through Hemisphere-Specific Priming: Cases From Choking Under Pressure, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 2012; DOI: 10.1037/a0029852

[3] Mathias Pessiglione, Liane Schmidt, Stefano Palminteri, and Gilles Lafargue et al. Splitting Motivation: Unilateral Effects of Subliminal Incentives. Psychological Science, (in press)

Also: Association for Psychological Science (2010, June 30). Is your left hand more motivated than your right?

[4] Geoffrey Brookshire, Daniel Casasanto. Motivation and Motor Control: Hemispheric Specialization for Approach Motivation Reverses with Handedness. PLoS ONE, 2012; 7 (4): e36036 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036036

[5] David Frayer, Marina Lozano, Jose Bermudez de Castro, Eudald Carbonell, Juan Luis Arsuaga, Jakov Radovcic, Ivana Fiore, Luca Bondioli. More than 500,000 years of right-handedness in Europe. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 2011; 1 DOI: 10.1080/1357650X.2010.529451